From 2001 to 2003 I traveled the world for free, thanks to my own social network www.letmestayforaday.com and the thousands of people from all over the world who invited me over through that website. In return, my compensation for free accommodation for one night, I published a daily travel diary on the website. The entire diary of over two years of traveling is still online and was published as a Dutch travel book in 2004. Below is an English translation from a chapter in this book, which became relevant after the release of the movie The Grizzlies, filmed in Kugluktuk one year after my visit in 2003.

First, some background on the location. Yellowknife is situated at the North end of the Great Slave Lake and came to being after the gold rush of 1934. Yellowknife consists of the Old Town, built on a small island, and New Town, spread out over the bare, frozen tundra’s of the North. During the long and dark winter days, the Great Slave Lake becomes a ring road for Yellowknife and people drive over the vast ice pack. After the slow decline of the gold findings, pure diamonds were found decades ago and the city quickly developed into one of the most important diamond supplier worldwide.

Tourism, mostly from Japan, is the other important means of income in Yellowknife. Tourists enjoy the excursions such as Walking on the Ice and visits to the local diamond mines. Most Japanese, however, travel all the way to the cold North of Canada for the Northern lights; apparently it makes them fertile and brings good fortune to their relationship. This is why annually 150,000 Japanese choose Yellowknife as destination for their honeymoon.

One day after traveling all the way from Grande Prairie in Alberta, hitch-hiking 775 kilometers north for 16 hours, I had arrived at the end of the MacKenzie Highway in Yellowknife. This is where the roads northbound simply stopped.

In Yellowknife was staying with Jeff and his family. He had helped me with my transport from Hay River, by persuading the bus company to sponsor my bus pass. Jeff is the founder and general manager of the most northerly situated Internet provider in Canada: ssimicro.com. He proudly showed me how his company provides the many isolated communities in the north with wireless internet (this is 2003, remember?). ‘A transmitting tower with a satellite connection can connect an entire village to the World Wide Web,’ he said. ‘You place a special card in your computer, and that will create your connection. Internet will not only be great for emailing, but especially for live-stream meetings with other communities or companies.’

I found it to be extremely useful to stay with managers of large companies, because they were in close contact with their colleagues of other companies. Jeff knew someone on the executive board of the only airline that flew to the town of Kugluktuk, Nunavut!

I had told them all about my personal challenge to visit the arctic North of Canada. If only I could experience the way people live and survive there, what keeps them busy, and how they maintain a life that seemed impossible from my point of view! I had one invitation from Kugluktuk, a town on the coast of the Arctic Ocean. The woman who had invited me was a teacher at the local high school and she had told me long ago that the only way to get there was by airplane.

‘No problem,’ Jeff said, and he made a few phone calls from his office, explaining my project to some of his friends. ‘First Air is giving you a free round trip to Kugluktuk worth 900 dollars.’

I immediately phoned the school in Kugluktuk to tell teacher Rebecca that I would be stopping by. She was ecstatic and asked me for a favour by email: ‘We’ve got two small shops in this town, and most of the food is five times as expensive as it should be, and usually the perishable date is long gone. Would it be possible to bring some groceries with you from Yellowknife?’

Jeff took me along to the local community store to stock up on groceries. Rebecca had emailed me a long shopping list and because Jeff was able to advance the money for Rebecca, everything went along in the plane in large cardboard boxes. I was finally heading to Kugluktuk!

From the plane I could see the landscape changing from the barren woods to treeless tundras with a thick layer of snow without any contrast. I was unable to tell whether the plane was flying at a high or low altitude, or whether I was flying over a mountain or field. I just saw white.

The night before I had looked up the weather forecast: maximum temperatures in Kugluktuk would be -25 degrees Celsius ‘at most’. And if the wind picked up, it could even drop to ‘no less than’ -40 degrees. The temperature in Yellowknife was already around -15 degrees Celsius. But in Yellowknife, -15 degrees felt just like a Dutch winter with a temperature around freezing point. So, I should survive it without any problems, right?

It was around noon when the plane landed on a small airstrip. As far as I could see through the window, I found myself in a completely white and desolate no man’s land. I got off the plane and walked towards the only building nearby. The wind was so cold: it seemed to cut straight through me. Wherever I looked, all I could see was a moonscape in which someone had been shaking around the powdered sugar for a long time. After a few breaths, I could no longer feel my nostrils. The inside of my nose had frozen up immediately.

A chock-full van took me to the village with its pattern of dead end roads. The van stopped in front of a small, brown, duplex building. A door swung open, and Rebecca waved at me. ‘Welcome to Kugluktuk!’

Now shortly about this Kugluktuk. Kugluktuk is situated in Nunavut which, on the 1st of April 1999, became Canadian territory. Nunavut spans a surface area of over 22 (!) square kilometers: from the North pole past Greenland, and the entire area north and west of the Hudson Bay. The smallest hamlet has only 25 residents, and the largest town and capital city of Nunavut, is Iqaluit on Baffin Island, with around 6,000 residents. The total headcount of inhabitants of around 28.000 is remarkable when you consider that the area spans one-third of entire Canada.

Nunavut is the country of the musk ox, polar bears, Caribou buffaloes, and the infinite amount of kilometers of well-stocked lakes and rivers. Mankind is a minority and does not have much influence. It is therefore understandable (and rather funny) that there is only 21 kilometers of highway in the entire area.

Nunavut literally means ‘our land’. In the Inuinnaktun language of the Inuit people, derogatorily called ‘Eskimos’ by outsiders – the native Indian word for ‘eaters of raw meat’. The people call themselves Inuit, which translates as ‘real people’ with Inuk as singular noun. Words such as ‘kayak’ and ‘iglo’ are typical Inuit words. The Inuit speak two main languages, apart from the many regional dialects: the Yupik of the Inuit in Siberia and Alaska, and the Unuktituk in Canada and Greenland.

The Inuits are different from the original inhabitants of Canada: they are the people that traveled under hostile natural circumstances, with their dog sleds and kayaks. Until around fifty years ago, they would spend the night in igloos in winter, and skin tents in summer.

Rebecca house was a two bedroom apartment with a large living room and open kitchen. In her warm house, she unpacked the boxes of groceries that I had brought with me. With every item she unpacked she started to shine more and more. ‘Oh, bananas! Oh, chocolate cookies! Oh, marinated salmon steaks! Oh no, chocolate-vanilla-strawberry ice-cream! Delicious! It is almost like Christmas!’

Rebecca had lived in Kugluktuk for three years already. She originated from the westernmost province British Columbia and was offered the opportunity to work as a teacher all the way north.

‘Life is so different here. There is a totally different culture and we, the white minority, try to educate the natives. Only fifty years ago the Inuit still lived in igloos and to support themselves as they hunted elks, oxes, and polar bears. In the fifty years that followed, they acquired microwaves, satellite television (with Inuit television stations), internet, and DVD-players! Some families have been watching Days of Our Lives on television in the afternoon for years.’

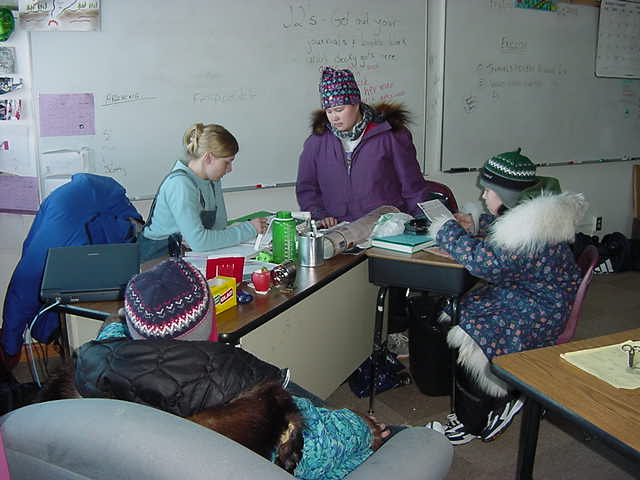

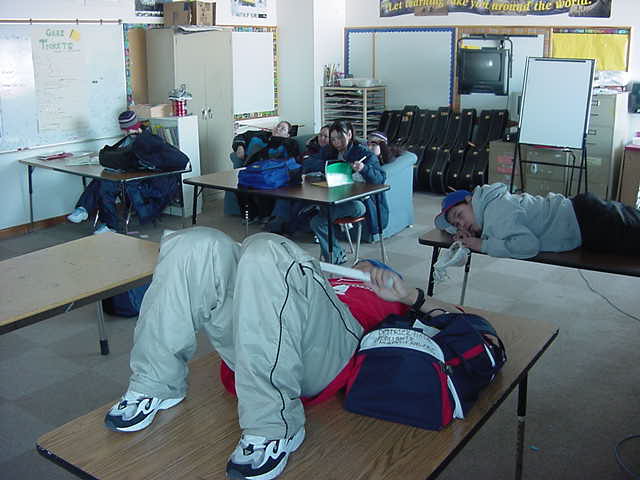

I did not understand what she meant about the other culture until after she took me to her school. Rebecca taught science, English, mathematics, art, music, health education and was mentoring a class. When she introduced me to her class, some students fell silent with shyness while others dropped their jaws with amazement. It was clear that they were not used to receiving visitors from outside the village. Or from The South, as they called it. ‘You can ask Ramon anything you like,’ Rebecca said to her class, ‘as long as it stays decent.’

Only one child in the class was white, all others were Inuit children. Rebecca told me she was worried about her class because her sixth grade was still on the level of a fourth grade. ‘They think differently here. It’s not like they ask you something, and then you answer them, like we are used to. They just don’t do that. And among themselves they use their traditional sign language to which I’m only partly familiar with. Raising your eye brows means ‘yes’, while eyes that are nearly closed mean a ‘no’.’

It was fascinating to watch the interaction between the children and teacher, while I was sitting at the side. On the wall there were posters of green trees and rain forests. No trees grow here in the north.

The teachers of the school explained to me that the school system in Nunavut could be compared to colonialism. ‘We are the white people who enter their lives and culture. The parents never went to school, so the children aren’t taught the importance of education.’

Rebecca does not give her pupils homework. ‘They won’t do their homework anyway. They get assignments that they have to do in class, and even then they sometimes won’t do it.’

The other problem is alcoholism. ‘Alcoholic parents can’t raise children. Teenage pregnancies occur and children are born whose mother was always drunk. It’s something that you’d rather not think about, but I wouldn’t be surprised if many children at school only had pulp for brains.’

In the corridors at the school, the teenage students were all too pleased to touch me and talk to me. Down the hall it was already ‘Hey Ramoooon’. They told everyone who would listen that I ‘travel the world for free’. But I could tell from the look on their faces that they had no idea what ‘the world’ meant. They asked me my age and whether I was Rebecca’s husband; it was the kind of gossip that you get in a town that can only be departed by plane.

After this day in school, I stopped by the post office with Rebecca and her colleague Jeanny to pick up some mail that had arrived with my airplane. Jeanny had a subscription to The Globe and Mail on Sunday but always received the newspaper two weeks late. On our way back to Rebecca’s house we walked through the white, icy streets of Kugluktuk. I felt my face freeze while I had made sure my head was covered with my balaclava.

Rebecca had to walk her husky dog Nanuk (Inuktitut for polar bear) and invited me for a ride on her double-seat skidoo, her motorized sled. In order to defy the cold, Jeanny lent me her fur parka. What a giant difference animal skin makes!

And just like that, we left the land of the living in Kugluktuk. Nanuk ran happily alongside us. We drove through the valley of the frozen Coppermine River, where we could freely play with the skidoo. With me behind the wheel the engine effortlessly reached 120 kilometres per hour. Rebecca held onto me tightly and pointed out some steep riversides she wanted me to race up against. I accelerated and with high speed we climbed the 20 meter wall. Once we had reached the top, we jumped up several meters more, at which point the skidoo decided to leave us. With a thump we landed deep in the snow, with the skidoo 20 meters away, followed by an unstoppable fit of laughter. It was so cold, it was so thrilling and did I just race up a snowy riverside?

I could no longer feel the tip of my nose. With my normal shoes on, my feet too were now getting cold. ‘Then it’s better to go home quickly,’ Rebecca said. I don’t know whether it was wise to race the skidoo back home at a high speed, because on our way we nearly froze ourselves in the cold wind. The thermometer of the skidoo read -40 degrees, but my body felt much colder.

As soon as we were back in Kugluktuk, Rebecca turned on the faucet with hot water and ordered me to put my frozen feet in. After ten minutes they still felt numb. ‘The feeling will come back soon,’ Rebecca said, while telling horror-stories of frostbite and she explained how your fingers and toes can just fall off when that happens. Amazing. Thanks.

With my feet in the water I asked Rebecca what she thought of life here. After half a day, I already knew how ordinary everything really was. Kugluktuk could have been a suburb of Yellowknife, the people have everything they need, and skidoos replace arctic quad cats in winter. It was like every other small town with 1,300 inhabitants and where everyone knows each other.

Kugluktuk has a primary school, a secondary school, two supermarkets, a post-office, two churches, a fire-station, a town hall, a nursing home, a sports hall, a youth center, and a hang-out spot for kids. Pubs and theaters had no place here and the biggest event is the Bingo night, every fortnight, in the library of the school.

‘And when the schools are closed during the holidays, there is a curfew because otherwise the children would hang around on the streets until late at night. At ten o’clock there is a loud siren and no-one under the age of sixteen is allowed to be on the street.’

Jeanny stopped by for dinner because there was salmon on the menu. While enjoying the warm cake bread, feta salad, and salmon, the girls could not stop boosting the delicious food I had brought along. ‘To add variety to our meals, we decided to cook for each other,’ Rebecca told me about her cooking-pact with Jeanny. ‘But a meal like this is very special. Normally this is unthinkable!’

That night the air had a dark-blue hue and we drank tea near the fireplace. A month from now, during summer, the sun would not set at all anymore for over a month. Rebecca said I was welcome to stay for as long as I liked. She only hoped I would not get to bored while she was working during the day.

I was not bored at all. I could have a lie-in every day, which even turned out to be a necessity for newbies. The dry air and cold weather demanded quite an adjustment from the body. I noticed it, even in the morning, as I was walking Nanuk through the snow. After 15 minutes I was exhausted!

Rebecca had left her skidoo for me to use, so I took it rides whenever I wanted. I left Kugluktuk via the beach, and raced at high speed over the snow-covered ice of the frozen sea that borders Kugluktuk. Behind me, Kugluktuk was getting smaller and smaller, and when I stopped shortly to look around me, all I could see were the tracks of the ski-doo behind me. As far as I could see, I saw the white of the frozen sea, and the blue of the sky. Above me, the sun shone faintly, but the temperature did not let up to -25 degrees.

On another day the school was presenting the school reports to all the students, and it was very different from what I was used to. The pupils did not take their reports home, because they would not show them to their parents anyway. Both pupil and parents were invited to discuss the child’s progress with the teacher. That way, not only are the parents involved in their child’s education, but they also get to see the school from the inside, as well as their child’s work.

After Rebecca had finished the reports, she suggested to have some pizza. ‘Shall I order a pizza,’ I said jokingly. In a circle of 600 kilometers there was not a pizzeria in sight. ‘We did something like that once,’ Rebecca told me. ‘A while ago the teachers were so desperate for Kentucky Fried Chicken’s chicken wings that we called the KFC-store in Yellowknife with the question whether they could get us chicken wings. They were fine with that and sent us a few giant buckets by plane. Of course, the food was frozen solid and we would have to fry it ourselves, but eventually we had our own Kugluktuk Fried Chicken for a few days!’

Rebecca told me she did not want to stay much longer in Kugluktuk. ‘I want to see my parents in Calgary and after that I want to live in Vancouver with my boyfriend Gregory. After three years in Kugluktuk I am ready for a change.’

I was surprised by her confession because nothing gave the impression that she was not happy here. The fact that she was so far away from her boyfriend Cregory, who was a reporter for CBC-radio in Vancouver, would sometimes make her sad. ‘You have no idea what my phone bill is like,’ she said. ‘We call each other every day for an hour!’

‘But I also found out that my life is too much centered around teaching. Although I studied for it, being a teacher here is very different from being one elsewhere. As a teacher here, the entire community comes to me with their problems. If you help their children, you must also be able to help them. I am always Teacher Rebecca, and not just Rebecca, and sometimes that is difficult for me.’

That night I just had to visit the local hangout for the youth: The Arcade. The Arcade is founded by Jeanny, among others, to give children something to do in their spare time. They can buy candy there, rent videos and DVDs, play pool and computer games. Because of all the greetings (‘Hey Ramooooon, my friend!’) it took us a while to finally get in. There I saw something that looked like a packed trading floor with lots of screaming children who could not sit still, dressed in cool and hip clothes. Loud rap music echoed from the speakers.

The weekend rolled in and on Saturday Rebecca and I were invited by the Inuit-couple Richard and Grace to come along to their cabin by the river with them, their three children and grandchild. Father Richard is a hunter and hunts elks and foxes for their fur. The family is know in the town as the proud makers of cold resistant clothing, mostly completely made from natural fur.

For maximum protection against the cold, I was dressed up properly at their house. I wore a thermic layer under my regular pants and a windproof pair on top of that. But that still was not enough, so the family lent me an extra thick pair of skiing pants. My feet were inside a warm pair of furry boots and my hands disappeared inside furry gloves. No more frostbite for me!

Outside the temperature was -30 degrees Celsius and powder snow came swirling down. The journey to the cabin was fabulous. I was allowed to ride Rebecca’s skidoo and followed the group across he marshlands South-East of Kugluktuk. It was snowing so hard that all you could see was a wall of snow. Everybody kept to a maximum speed of only thirty kilometers per hour.

We arrived at the remote little house along the frozen river. Inside a battery and some gas heaters were started up and some ice from the river was melted for coffee and tea. In the cabin there were two tables with chairs and against the back wall were some beds pushed together. We warmed ourselves to each other and the heaters and soon we started to steam and saw the stars disappearing from the window.

In the cabin I was introduced to eating raw meat. Because the arctic area is frozen for most of the year, it is impossible to grow vegetables or grain. The traditional Inuit-food therefore consists of meat, fat, and fish. In the past, the Inuit life was centered solely around the hunting for food. Still, the most important food is seal meat and whale fat. They get their vitamins and minerals from whale fat and seal livers, which comparatively holds as much vitamin C as a lemon.

The meat and fat are consumed raw, or cooked. If the Inuit kill more animals than they can eat, the meat is dried for times when there is less food available. What is left of the animals, such as the fur, is used as insulation material for houses and clothing.

Are the Inuit not allowed to sell the remaining animal skins on the market? No, since Greenpeace started a campaign in which footage was shown of young, sweet baby seals being clubbed to death in a grueling way, it is prohibited to import animal skins in Europe and the USA. That the TV showed pictures of Norwegian poachers did not matter to the shocked viewers from all over the world. Nobody wanted to wear fur any longer, and the Inuit were portrayed as the enemies of those lovely seals. Thanks to Greenpeace’s campaign the fur-market collapsed and many Inuit were forced to live of welfare, which costs the Canadian government tens of billions of dollars.

Richard told me that the biggest threat for the seals was not the hunters but the global pollution. ‘As an Inuit I got very upset when we were told again and again by the Western world how we were supposed to live, while those same governments never understood our traditions or culture and hardly did anything to protect the environment.’

The strict diet of meat and fat was enough for the Inuit for many ages. Heart diseases, diabetes, and cancer are very rare there. From recent surveys it has even been proven that the Inuit, since they adjusted their menu more to Western habits, now suffer from decaying teeth and a long list of diseases, caused by the new diet.

Back Rebecca’s home, she spotted frostbite spots on my cheeks. Pieces of skin were frozen by the cold. ‘It’s not so bad, you won’t end up with scars,’ she said. ‘But you’ll still see it a few months from now.’ I was proud of my frostbite cheeks; it would remain a special souvenir from my visit to the arctic!

On Sunday I had been invited by Richard and Grace to visit them while they were ice fishing. Rebecca had planned to lie in and prepare classes for the week to come during the day, so I went out by myself. From the beach of Kugluktuk, I raced my skidoo across the snowed ice and drove to small spot in the distance. A few kilometers into the ocean, Richard and Grace were hacking holes in the ice with their children. With long sticks and iron pins there was plenty of hacking going on. I was received by sweaty faces. I was allowed to have a go and discovered that it was hard work. It took me more than thirty minutes before I had hacked a hole through the 2-meter-thick ice. Richard went home to pick up an electric drill to make more holes, faster. The family spoke mostly Inuktituk among each other and once in a while there would be a joke in English. In the meantime we were all squatted down above a 20 centimeter hole in the ice with a string.

‘Sometimes we catch forty fishes in an hour, and sometimes we go home empty handed,’ Grace said in broken English. ‘But is fun, yes?’

After three hours on the ice, I started to get really cold. After I had tried to warm myself by hacking holes in the ice, and having snow fights with the kids, I eventually had to return home again to warm up.

When I wanted to take a shower on Monday morning, I noticed there was no water from the tap. And only then I started wondering where the warm water was coming from when temperatures were below -45 at night.

‘Every week the water truck comes by,’ Rebecca told me. ‘It fills the electronically heated water tank behind the house. The sewage water is pumped away once a week by a garbage truck. So I suggest that you go outside looking for the water truck if you want to take a shower,’ Rebecca laughed. ‘Then you can walk Nanuk at the same time.’

On my last day at the school I had been invited to eat Karibu soup during the class of Domestic Skills. The school children gave me a warm sweater of the Kugluktuk Grizzlies, the local sports team, as a present. I had enjoyed my days in the North and nearly chocked up when I had to say goodbye.

Slowly, I had got used to life in Kugluktuk, the desolate town in the North of Canada, where everybody is welcoming, friendly and so polite to this foreign stranger that just came to visit for a short while, thanks to the network the internet gave and its users’ hospitality.

There is not much to gain in Kugluktuk, but also little to lose. I guess it makes everybody quite humble with what they actually have and how that all fits in life.

It was cold, but livable because of the extreme warmth of the people. I was there for one week and then flew off again to other remote areas of the Canadian north. But I have missed Kugluktuk since.

Rebecca finished the school year in Kugluktuk and moved back to Vancouver with her boyfriend Cregory in 2003. She got married in 2004, lives on Vancouver Island and is now a proud mother of three beautiful boys.